Modern data engineering is often described as a stack.

Ingestion feeds transformation. Transformation feeds orchestration. The warehouse feeds BI. Each layer has a purpose, a vendor, and an ever-expanding surface area of features.

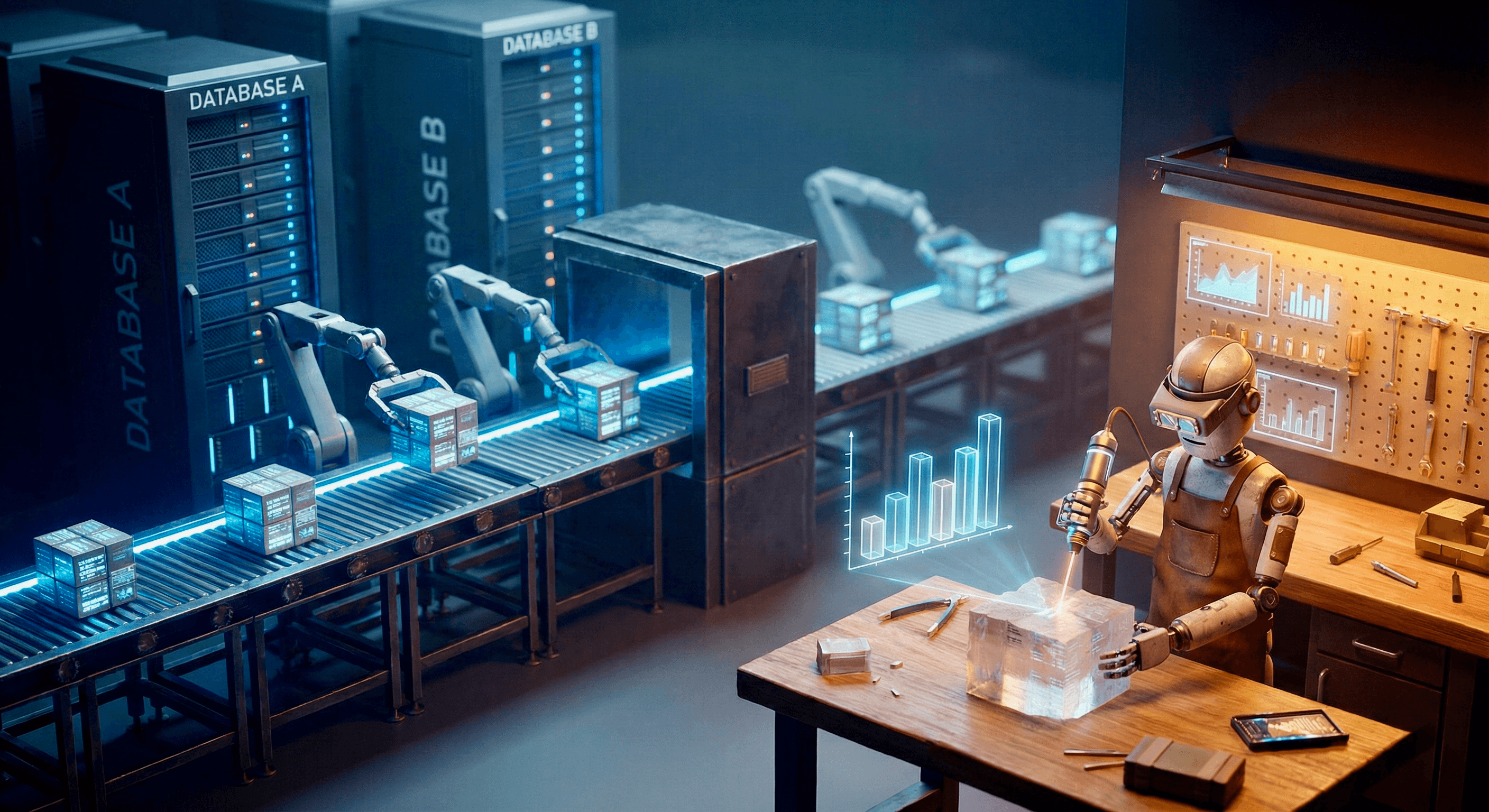

We didn’t build these assembly lines by accident. For a long time, they were survival. When compute was slow, storage was expensive, and querying operational systems was risky, the only reliable way to deliver analytics was to carefully control every step. Pipelines brought order to a fragile discipline.

But the constraints changed.

The architecture didn’t.

Today, we still build factories by default. We orchestrate complex pipelines and stitch together infrastructure before the work has stabilized. We optimize for control when the real constraint is learning speed.

What we need isn’t a better factory.

We need a workshop.

An environment that’s cheaper to run, faster to adapt, and responsive to questions that evolve faster than pipelines can. One that treats strong tools and cheap storage as leverage—not excuses to add more machinery.

This isn’t an argument against rigor.

It’s an argument for rethinking why we assume a factory is the starting point at all.

Why the Stack Made Sense — The Assembly Line Era

The modern data stack made sense because, for a long time, data work genuinely needed to behave like a factory.

Back then, our hand tools were weak.

Laptops couldn’t scan large datasets without grinding to a halt. Query engines were slow. Memory was tight. Storage was expensive enough that you couldn’t just keep everything around and figure it out later. If you wanted to analyze serious volumes of data, you needed heavy machinery—large cloud clusters—and you had to use them carefully.

So teams built assembly lines.

Data had to move off operational systems, not because it was elegant, but because it was necessary. Production databases weren’t safe places to experiment. Running analytical queries against them risked outages, lock contention, or runaway costs. The safest option was to extract the data, reshape it, and push it somewhere designed for analysis.

This is where the conveyor belts came in.

Moving large amounts of data was expensive, but running the line was often cheaper than storing raw material indefinitely. Instead of keeping every bolt, panel, and scrap of metal, teams repacked data into standardized parts. They summarized aggressively. They threw away what they couldn’t afford to keep. The output was smaller, cleaner, and far easier to work with downstream.

That repacking step is what made analytical warehouses viable.

By the time data reached the warehouse, it wasn’t raw material anymore—it was a kit. Tables were organized around facts and dimensions. Star schemas emerged because they fit the factory model perfectly: pre-joined components, standardized shapes, predictable performance.

In factory terms, star schemas were pre-cut parts laid out on a jig.

They reduced guesswork. They made joins cheap. They ensured everyone was assembling answers from the same components, in the same way. That consistency mattered more than flexibility, because flexibility was expensive and slow.

Orchestration existed for the same reason factories need timing and coordination. Jobs had to run in order. Dependencies had to be respected. A missed step could spoil the entire batch. Scheduling and monitoring weren’t luxuries—they were how the line ran without constant human supervision.

The strength of this model wasn’t elegance.

It was control.

Assembly-line data engineering traded adaptability for reliability. It front-loaded work so queries could stay fast. It reduced risk by separating systems. It made analytics possible at a time when the tools simply couldn’t handle ambiguity or late decisions.

Given the constraints of the era, this was the right architecture.

The factory wasn’t overengineering.

It was survival.

The real question isn’t why we built assembly lines.

It’s why we’re still building them now that the tools in our hands look nothing like they used back then.

What Changed

What changed wasn’t just the technology.

It was the economics of data work—and the pace of the questions it needed to answer.

The hand tools got dramatically better.

What once required heavy cloud clusters can now run comfortably on a laptop. Modern CPUs, abundant memory, fast local disks, and engines like DuckDB mean you can scan, join, and aggregate large datasets without precomputing everything first. The tools that used to struggle with basic cuts can now power through complex work on demand.

In factory terms, the power tools finally arrived.

And once individual tools are strong, the logic of the assembly line starts to break down. Assembly lines exist to compensate for weak tools. When every cut is slow and expensive, you want to do it once, do it early, and never touch the raw material again. But when cuts are fast and cheap, you don’t need to pre-shape everything before you know what you’re building.

Storage flipped at the same time.

For a long time, conveyor belts made sense because storage was expensive. It was cheaper to move data through the line, reshape it, summarize it, and throw away what you couldn’t afford to keep. Today, storage is absurdly cheap compared to orchestration and coordination. Keeping multiple copies of data—raw, lightly processed, reshaped for different needs—is often cheaper than maintaining the machinery required to constantly reprocess it.

It’s now cheaper to keep the lumber than to keep the line running.

Along the way, many teams learned something uncomfortable:

we don’t actually have “big data.”

We have a lot of data, but we use very little of it to make decisions. Most logs are never queried. Most events are never revisited. Most raw exhaust exists just in case—not because it actively drives insight.

Factories are built to process everything that comes in.

Workshops don’t work that way. They pull the material they need, when they need it, and ignore the rest. When tools are fast and storage is cheap, that selective approach stops being reckless and starts being rational.

At the same time, the nature of the work changed.

Teams don’t ask for the same report every quarter anymore. Questions arrive continuously and evolve as the business learns. The value comes from iteration, not from stamping out identical outputs. Assembly lines are optimized for stability; they’re terrible at exploration.

Changing a factory is expensive.

Adding a new station, rearranging the order, or reworking an output takes time, coordination, and approvals. By the time the line is updated, the question that justified it has often changed. The organization moves on, but the pipeline remains—now maintained out of habit rather than necessity.

Budgets tightened too.

The tolerance for infrastructure that mostly exists to manage itself has shrunk. Every additional tool adds cognitive load, governance overhead, and failure modes. Vendor consolidation becomes attractive not because platforms are perfect, but because fewer moving parts are easier to reason about, secure, and explain.

The business doesn’t want a perfectly tuned factory.

It wants answers—quickly, cheaply, and with enough confidence to act. That puts pressure on factory-style data teams, who are optimized for correctness and consistency, not learning speed.

So we end up in a strange place.

The work looks like a workshop—messy, iterative, and adaptive—but we keep reaching for factory solutions. We front-load decisions. We orchestrate pipelines for questions we don’t yet understand. We optimize for control when the real constraint is learning.

Not because it’s the best approach.

But because it’s the one we know.

The Anti-Stack Mindset

The anti-stack isn’t about rejecting discipline, tooling, or engineering rigor.

It’s about refusing to build a factory by default when the work doesn’t call for one.

Assembly lines exist to compensate for weak tools and expensive decisions. When every cut is slow and every mistake is costly, you front-load everything: define the final shape early, lock the process in place, and optimize for repeatability over learning.

But once the tools get stronger, that logic stops holding.

What follows aren’t rules or architectures. They’re principles — ways to decide when not to add machinery.

Principle 1: Prefer Strong Tools Over Long Pipelines

Power tools beat conveyor belts.

When query engines are fast and reliable, you don’t need conveyor belts just to move data into a shape downstream systems can tolerate. Every pipeline you add is machinery you now have to operate, monitor, and justify.

Long chains of narrowly scoped tools feel “enterprise,” but they often exist to protect weak components from doing work they could already handle. Fewer, stronger tools concentrate capability where it matters — at the point where questions are asked.

If a pipeline exists only so a dashboard doesn’t have to work, that’s a smell.

Principle 2: Defer Decisions Until the Question Stabilizes

Measure twice. Cut once. Don’t pre-cut everything.

Factories require certainty up front. Workshops don’t.

In modern data work, most questions are still forming when the first pipeline gets built. Shaping data too early locks in assumptions that haven’t been tested. Raw or lightly shaped data isn’t negligence — it’s optionality.

Upfront certainty often feels responsible. In practice, it’s usually premature commitment with better documentation.

Principle 3: Use Storage as a Buffer, Not a Liability

Keeping the lumber is cheaper than running the line.

Historically, raw material was expensive, so teams rushed to summarize and discard. Today, storage is cheap. Coordination is not.

Keeping multiple representations of data — raw, cleaned, reshaped for specific use cases — is often cheaper than maintaining a single, perfect pipeline that everyone depends on. Redundancy reduces coordination. Duplication can simplify systems.

Purity is expensive. Understanding is not.

Principle 4: Treat Orchestration as a Last Resort

Only time the line if you actually have a line.

In factory thinking, everything must be scheduled, ordered, and timed. Orchestration becomes a badge of seriousness.

But not all work is production work. One-off analysis doesn’t need a DAG. Query-time joins don’t need scheduling. Exploration doesn’t benefit from cron jobs.

If you’re spending more time debugging job timing than delivering insight, the machinery has taken over the work.

Principle 5: Optimize for Learning Speed, Not Throughput

Insights matter more than units per hour.

Factories optimize for volume, consistency, and uptime.

Businesses win by learning faster than their environment changes.

Perfect pipelines that answer yesterday’s question are less valuable than rough answers that arrive while the question still matters. Early in the lifecycle of a question, speed beats polish almost every time.

Stability is a later optimization.

Principle 6: Minimize Data Movement

Every forklift trip adds risk.

Each hop between systems adds cost, failure modes, governance overhead, and compliance complexity. This is why vendor consolidation keeps resurfacing — not because platforms are perfect, but because fewer hops are easier to reason about.

Stacks multiply movement. Platforms reduce it. When movement dominates cost, complexity compounds quickly.

Principle 7: Choose Open Materials Over Proprietary Machinery

Standard lumber beats custom molds.

You don’t escape lock-in by picking the “right” vendor. You escape it by owning the materials.

Open formats preserve optionality. They let you change tools without rebuilding the factory. Proprietary machinery hard-codes decisions into the shape of the work itself.

Materials matter more than machines.

Principle 8: Build Factories Only When the Work Earns Them

Assembly lines should be justified, not assumed.

Some workflows absolutely deserve factories. When the work is repetitive, stable, and high-volume, assembly lines are unmatched.

The mistake isn’t building factories.

It’s building them before the work proves it needs one.

The anti-stack isn’t anti-factory.

It’s anti-premature factory.

Build workshops first.

Let the work tell you when it’s time to pour concrete.

So What Does This Look Like in Practice?

In practice, the anti-stack starts with restraint.

You move the raw data somewhere safe and queryable, and then you ask the question directly. The query might be ugly. It might be inefficient. It might take two minutes to run. That’s fine.

You weren’t building infrastructure.

You were answering a question.

At this stage, performance doesn’t matter nearly as much as clarity. Pre-aggregating, modeling, and scheduling work before you understand the shape of the problem just front-loads assumptions. If the answer is needed once, or twice, or as part of an exploratory thread, the cost of waiting a minute or two is trivial compared to the cost of building and maintaining a pipeline that no one will ever reuse.

This is where factories get built too early.

The shift happens when the question stops being occasional and starts being habitual. When that same ugly query shows up everywhere. When it burns CPU every day. When it slows dashboards or frustrates users. That pain is the signal — not a failure.

Only then does it make sense to offload the work.

You pre-calculate the expensive parts. You materialize what’s repeated. You introduce scheduling and monitoring because the savings now outweigh the overhead. The factory earns its place not because it looks clean, but because it reduces real, recurring cost.

The mistake isn’t running inefficient queries.

The mistake is assuming inefficiency is always a problem worth industrializing.

The anti-stack mindset treats query-time work as a proving ground. If the work disappears, no harm done. If it sticks around, the path to a factory becomes obvious — and justified.

That’s how you avoid overbuilding without sacrificing rigor.

Factories Should Be Earned

The modern data stack wasn’t a mistake.

It was an answer to the constraints of its time.

When tools were weak, storage was expensive, and mistakes were costly, assembly lines were the only way to make analytics reliable. They brought order, predictability, and trust to a fragile discipline. Without them, many organizations would never have believed in data at all.

But the conditions changed.

The tools got stronger. Storage got cheaper. Questions started moving faster than pipelines could keep up. And the work itself stopped looking like mass production. What once required factories can now often be done with power tools, on demand, with far less machinery in the way.

Yet the instinct to build factories remains.

We still reach for stacks before we understand the work. We still orchestrate complexity to feel safe. We still treat structure as proof of seriousness, even when it slows learning and hardens assumptions too early.

The anti-stack isn’t a rejection of engineering.

It’s a refusal to confuse discipline with ceremony.

It asks a simpler question: What is the minimum machinery required to answer this question well? And just as importantly: What can we avoid building until the work proves it needs it?

Factories are powerful.

But they should be earned.

Most teams will do better starting in a workshop — learning, iterating, and shaping the work as they go — and only pouring concrete once the shape is clear.

Because in modern data engineering, the goal isn’t to keep the line running.

It’s to deliver insights.